The Construction Advantage

Thomas Jefferson Has An Important Reminder For You About Mechanic’s Liens

By Zachary Brandwein

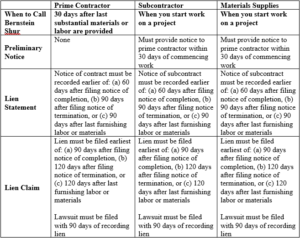

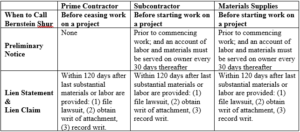

Thomas Jefferson is not only one of the Founding Fathers of American democracy, but also arguably the founding father of the American mechanic’s lien.[1] Most contractors, subcontractors, and materials suppliers know that a mechanic’s lien is probably the best leverage in their legal toolkit to get paid for a job well done. And as many of you expand beyond the reach of your home states, we thought we would remind you of the most important thing you need to know about mechanic’s liens – when to call us. So, in Thomas Jefferson’s spirit, Bernstein Shur’s Construction Group wants to provide you with a quick chart that you can print out with the deadlines you need to know about for mechanic’s lien in ME, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

Massachusetts Mechanic’s Lien Deadlines

New Hampshire Mechanic’s Lien Deadlines

[1] A Practitioner’s Guide to Construction Law, John G. Cameron, Jr., 2000, American Law Institute-American Bar Association Committee on Continuing Professional Education.

Dealing With Varying Weather Conditions During Construction

Differing site conditions and unusually severe weather are two of the most common sources of construction litigation. Sometimes, when groundwater levels cause construction complications, it can be difficult to determine how to classify the issue. This challenge was recently addressed in a decision by the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals (the “Board”) in Appeal of – Tidewater, Inc., 2018 ASBCA No. 61076, where the Board denied a contractor’s Type I claim for differing site conditions, when rain caused groundwater levels to rise substantially – resulting in increased costs and project delays.

There, Tidewater, Inc. (Tidewater) contracted with the United States Corps of Engineers (the “Corps”) to build an addition at the Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana over the period of 730 days. In preparation for construction, around February 25, 2013, Tidewater retained a geotechnical engineer and received a report indicating that “Groundwater was observed at 19 feet [and] Groundwater may be present at different depths during other times of the year.” Based upon this report, Tidewater’s design for the renovation’s foundation included straight shaft concrete piers.

The Corps then suspended the project due to funding issues. Seven months later, on June 9, 2015, Tidewater remobilized and began pier drilling activity, only to discover that the water table had risen drastically to 9 feet below the surface. Just six days later the groundwater level measured at 7’-6” below the surface. As a result of this rain, and the variance in the site conditions (i.e. groundwater level), Tidewater was forced to abandon the use of straight shaft concrete piers, utilizing helical piers instead.

On July 26, 2016, Tidewater submitted a certified claim to the contract officer for the Corps, requesting an additional $726,669.27 in Contract Price, and 215 days in Contract Time. Tidewater’s claim was summarily denied, and it then appealed the decision to the Board, claiming that it was entitled to these changes as a result of Type I differing site conditions.

Type I differing site conditions consist of “subsurface or latent physical conditions at the site which differ materially from those indicated in the contract.” FAR 52.236-2(a)(1). Tidewater argued that when it commenced, work encountered “the fifth wettest month on record for the . . . area, with 10.97 inches of rain.” Tidewater alleged that the soils were “significantly saturated” and “materially different” in 2015 from when it bid the project in August 2012.

In denying Tidewater’s claim, the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals looked to Turnkey Enterprises, Inc. v. United States, 597 F.2d 750, 754 (Ct. Cl. 1979) and its progeny, which held that:

Generally, the government, under the standard Differing Site Conditions [clause], does not assume an obligation to compensate a contractor for additional costs or losses it occurs resulting solely from weather conditions, which neither party expected or could anticipate and note from any act or fault of the government. Weather conditions generally are considered to be acts of God.

Moreover, the Board found that Tidewater failed to allege a Type I differing site condition because it did not allege what contract indications, if any, regarding subsurface soil conditions constitute the predicate for its claim. Tidewater was only able to demonstrate that there was a discrepancy between the guidelines for the RFP, which indicated an average annual rainfall of 46.6 inches, and the actual annual average of 51.36 inches. The Board held that this statement from the guidelines was not on its face a warranty regarding future rainfall and was nothing more than a cautionary note regarding past rainfall.

The simple takeaway: know the site and know the impact that seasonal weather can have in that area. When in doubt, changes in groundwater levels do not justify a Type I change absent explicit representations in the contract.