The November Construction Advantage

In this month’s The Construction Advantage, Conor Shankman reports on a lien claimant saved from its own lien waiver, Meredith Eilers explains the UCC’s warranty for future performance, and Mike Bosse advises on a recent ME decision where the trial court used post-trial proceedings to determine a trial court judgment. We hope you enjoy this issue of The Construction Advantage!

Cashman v. West Edna Associates

In Cashman Equipment Company v. West Edna Associates LTD., the Nevada Supreme Court held that an unconditional release between a first tier contractor and a third tier contractor (sub-subcontractor) is void when payment fails to clear the bank – even if payment was issued by a second tier contractor (subcontractor).

An examination of the facts provides additional clarity.The Court acknowledged that this might require first tier contractors to issue payment twice (both to the insolvent second tier contractor and then to the third tier contractor) to avoid potential mechanic’s lien claims. However, the court also advised that double payment could be avoided by simply requiring second tier contractors to obtain payment bonds.

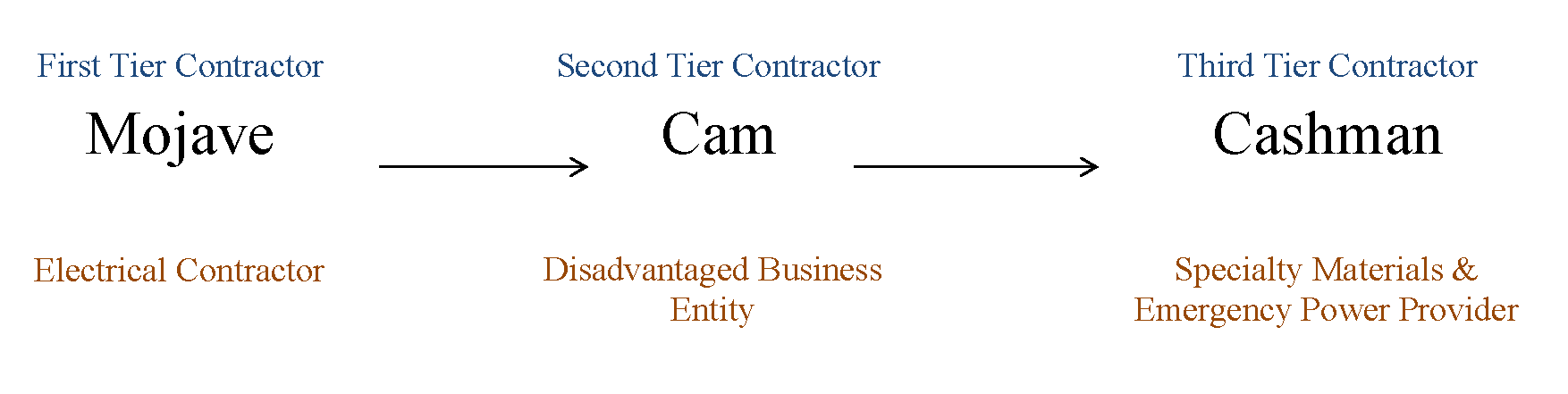

In Cashman, Mojave, an electrical contractor was hired to work on construction of the new Las Vegas City Hall. Mojave hired an intermediary entity named Cam solely to satisfy a disadvantaged business enterprise requirement. Cam’s primary role was to contract with Cashman to provide specialty materials and emergency power.

Upon completion of the job, Cashman provided an unconditional release to both Mojave and Cam in exchange for payment and then Mojave provided payment to Cam. That payment was intended to flow through Cam to Cashman for the actual labor and materials. But, while Mojave’s check to Cam cleared the bank, Cam’s check to Cashman bounced – Cam’s owner having apparently absconded with the money. Cashman then filed a mechanic’s lien for $755, 893.89, and brought suit to enforce.

While the trial court held that Cashman’s mechanic’s lien claim was barred by its unconditional release, the Nevada Supreme Court held otherwise, instead holding that when a payment fails any waiver or release it is void – regardless of who it is issued to. The purpose of Nevada’s mechanic’s lien statutes is to ensure payment to those who supply materials and labor on a project, therefore Nevada’s public policy disfavors the enforcement of the unconditional release is this case. As a result, Cashman was entitled to pursue its claim.

In response, Mojave claimed that any award to Cashman should be reduced using an equitable fault analysis. The trial court embraced this logic and determined that while Cashman has an innocent victim, it was also 66% responsible for Cam’s failure to pay, and therefore entitled to only $197,051.87 of its total mechanic’s lien claim. This logic was overturned on appeal, where the Nevada Supreme Court reasoned that because mechanic’s liens are the product of statute, equity jurisprudence was no place in determining the rights of a mechanic’s lienholder.

As we often say, do not sign unconditional lien waivers if you actually have not been paid. Instead, lien waivers should state that their validity is conditioned on payment actually happened. Such a statement would have avoided the mess that the case ended up being, although the Nevada Supreme Court ultimately reached the right result.

Warranties for Future Performance: Extending the Four-Year UCC Statute of Limitations Is No Easy Feat

ME’s Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) imposes a four-year statute of limitations on claims for breach of warranty, unless the warranty explicitly extends to future performance. Typically, building materials, such as lumber, are considered “goods,” the sale of which is governed by the UCC (if the value of the goods is $500 or more). The clock starts running on a breach of warranty claim when tender of delivery is made, not when any defect that serves as the basis of the claim is discovered and implied warranties, by their very nature, do not explicitly extend to future performance. Therefore, any claim for breach of warranty related to building materials is time-barred four years after the goods are delivered, unless there is an express warranty guaranteeing certain future performance of the goods, and discovery of the breach must await the time for that performance (i.e., a guarantee that a product will be free of all defects for a certain period of time).

Recently, the Third Circuit considered exactly what is required for a warranty to “explicitly” extend to future performance. In a case originating in the U.S. Virgin Islands, MRL Development I, LLC v. Whitecap Inv. Corp., 823 F.3d 195 (3d Cir. 2016), a lumber buyer sued the retailer, wholesaler, and wood preservation treatment company claiming that the lumber he purchased for a deck on his vacation home decayed prematurely. The lumber was purchased between 2002 and 2006 and the plaintiff began replacing boards in 2010, but he claimed he did not discover the full extent of the problem until 2011 and the plaintiff filed his lawsuit in 2013. The Third Circuit concluded that the plaintiff’s breach of warranty claims were time-barred by the Virgin Islands UCC because there was no warranty explicitly extending to future performance of the lumber. Although the plaintiff testified that he had relied on the defendants to provide him with material suitable to his project, he was unable to recall any specific guarantees from the defendants. Before the lawsuit, the plaintiff had never been in contact with the wholesaler or wood treatment company at all; he was not told by anyone associated with the retailer that the lumber was treated in a certain way or would last for a certain amount of time; he did not request any specific treatment; he could not recall exactly what the tags on the lumber stated; and none of the invoices from the retailer to the plaintiff made any warranty statements. The court held that these facts were wholly insufficient to support a claim for a warranty of future performance.

The court did state however what it expected to see in order for there to be a viable claim for a warranty for future performance. It stated that “explicit” means “distinctly stated,” “plain in language,” and “unequivocal.” The court said that they would look for language “which is so clearly and distinctly set forth that there is no doubt as to its meaning.” Based on these standards, the facts present in this case were not close, and the bar to achieving a warranty of future performance, at least in the Third Circuit, appears to be a high one.

Trial Court Reaches The Right Result With Post-Trial Affidavits

In the recent ME Supreme Court case of NDC Communications, LLC v. Kenneth Carl III, the ME Supreme Judicial Court wrestled with the strength of trial court evidence and whether it was enough to sustain the judgment in a construction matter. The parties in this case had an unusually complex set of agreements to develop a piece of land in Kenduskeag, ME. The work, unfortunately, was undertaken without a written contract and when the working relationship broke down, NDC filed a complaint between parties that it was owed substantial funds from Carl and asserted a mechanics lien. Carl counterclaimed against NDC for breach of contract, claiming that he was owed monies back.

At the conclusion of the jury-waived trial, the court issued a 13-page order with an extensive set of findings in favor of NDC. The trial court concluded, however, that without argument from the parties, the court could not determine how much Carl owed to NDC, and the trial testimony was conflicting and without clarity about what amount was owed. The court asked NDC to submit an affidavit setting forth its calculation of damages based only upon information that had already been admitted at trial. The court then allowed Carl’s counsel to submit an opposing argument based upon the trial evidence. After those briefs were submitted, the court entered judgment in favor of NDC enforcing its mechanics lien in the amount of $336,681.24.

Carl argued on appeal that his due process rights were violated by the post-trial procedures that the court used to determine the amount of damages. The Supreme Judicial Court rejected the argument, principally because the trial court had ordered that the affidavits could only include evidence that had already been admitted at the trial. Thus, the affidavit was merely a summary of damages evidence that had already been presented, albeit in a chaotic manner.

This is an unusual Supreme Court case in ME but it demonstrates the latitude that a trial judge has, particularly in a jury waived case, to determine the amount of damages in a construction dispute. Faced with a confusing underlying record, the court ordered both sides to present summaries of their best evidence in dueling affidavits. The ME Supreme Judicial Court found no due process concerns with doing so and concluded that the trial court had appropriately used this technique of post-trial arguments in order for the court to determine the damages owed.